It may be news to many workers that the Ontario Human Rights Code (the “Code”) protects against discrimination based on family status. “Family Status” is defined in the Code as “the status of being in a parent and child relationship”. The Federal Court of Appeal has emphasized the importance of ensuring that workers are not discriminated against because of their family status:

“Indeed, without reasonable accommodation for parents’ childcare obligations, many parents will be impeded from fully participating in the work force […] The broad and liberal interpretation of human rights legislation requires an approach that favours a broad participation and inclusion in employment opportunities for those parents who wish or need to pursue such opportunities.” (Johnstone, para 66)

A recent decision by the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (“HRTO”) in Misetich v Value Village Stores Inc (2016 HRTO 1229) (“Misetich”) has reopened the debate over which test courts and tribunals should apply to determine whether there is discrimination based on family status. Previously, there were several different tests in different jurisdictions, but the law appeared to be somewhat settled in 2014 by the Federal Court of Appeal in Canada v Johnstone (2014 FCA 110) (“Johnstone”). However, the HRTO in Misetich explicitly rejected that approach, instead favouring a more traditional discrimination analysis.

The Federal Court of Appeal’s decision in Johnstone involved a worker who worked overnight and rotating shifts, and was unable to find childcare. The Court found that her employer violated her rights when it refused to accommodate her. The Court outlined a test that it said should be applied flexibly and contextually. In its view, there is discrimination where:

- The child is under the care/supervision of the worker seeking accommodation;

- The childcare obligation at issue engages the worker’s legal responsibility for the child (not a personal choice

- The worker made reasonable efforts to meet the childcare obligations through reasonable alternatives, and no such alternative is reasonably accessible;

- The impugned workplace rule interferes in a manner that is more than trivial or insubstantial with the fulfillment of the childcare obligation.

In Misetich, a worker developed an injury that prevented her from performing certain physical work. Her employer sought to accommodate her by assigning lighter duties. However, the accommodation required her to work on evenings and weekends. The worker informed her employer that this accommodation would not work because she had to prepare meals for her elderly mother in the evenings. The employer asked for more details regarding the elder care required and whether the worker had explored other options. The worker refused to provide more detail. The worker did eventually provide a short doctor’s note, but the employer continued to seek more specific evidence regarding the elderly mother’s care needs, and whether the worker had explored other reasonable care options. The worker was eventually terminated on the basis that she had abandoned her position.

While the HRTO acknowledged that not every negative impact on family obligations constitutes discrimination, it nevertheless concluded that a distinct test different from other areas of discrimination is not required.

The HRTO outlined five reasons to support its position:

- The test for discrimination should be the same in all cases and there is no principled basis for developing a different test specifically for family status discrimination.

- The unsettled law on family status discrimination causes uncertainty, and inconsistent outcomes.

- Having different tests has created a higher burden for workers claiming family status discrimination.

- The tests that exist are difficult to apply in the context of eldercare because the law does not place the same legal obligations on workers to care for elderly parents as it does for children.

- The HRTO did not agree with other decisions that in order to prove discrimination based on family status, a worker must establish that he or she could not self‑accommodate the adverse impact caused by a workplace rule (self‑accommodation is not part of the analysis for other areas of discrimination).

The HRTO’s fourth point is particularly important considering that workers are increasingly providing care as baby-boomers age. It will be important for the law to ensure that employers and workers can work together on accommodations for situations where a worker needs to take care of an elderly parent.

Rejecting the Johnstone test, the HRTO applied the general test that applies in other areas of discrimination. The HRTO described its test for family status discrimination as follows:

“In order to establish family status discrimination in the context of employment, the employee will have to do more than simply establish a negative impact on a family need. The negative impact must result in real disadvantage to the parent/child relationship and the responsibilities that flow from that relationship, and/or to the employee’s work. For example, a workplace rule may be discriminatory if it puts the employee in the position of having to choose between working and caregiving or if it negatively impacts the parent/child relationship and the responsibilities that flow from that relationship in a significant way.” (para 54)

The contextual nature of the analysis means that the decision maker will consider factors such as whether the worker is a single parent in assessing the impact of the employer’s position. Once prima facie discrimination is proven, the burden shifts to the employer to show that there is a bona fide occupational requirement or that accommodation would cause undue hardship.

In Misetich, the HRTO concluded that the worker failed to show that she was discriminated against. In this case, the HRTO found that the worker made bald assertions which failed to provide her employer with sufficient detail for it to understand her needs and the worker’s ability to provide meals for her mother was not adversely affected by the proposed schedule because she could have changed her meal preparation process.

While the Johnstone decision remains good law for federally regulated employees, the Misetich decision has reopened the debate regarding the proper test for family status discrimination.

Regardless of which test applies, it is important for workers to know that employers have an obligation to work with them to find appropriate accommodations that meet eldercare and childcare needs. However, workers need to be aware that they must do more than make bald assertions and must provide sufficient information to their employer to substantiate their care responsibilities. Workers who need accommodation should be open with their employers about the extent of their needs and should be prepared to be flexible in finding a solution that works for everyone.

The lawyers at Jewitt McLuckie & Associates LLP have extensive experience with discrimination and accommodation issues. If you need advice on being accommodated by your employer, please contact us today at (613) 594-5100.

Article: Joshua Nutt (Articling Student)

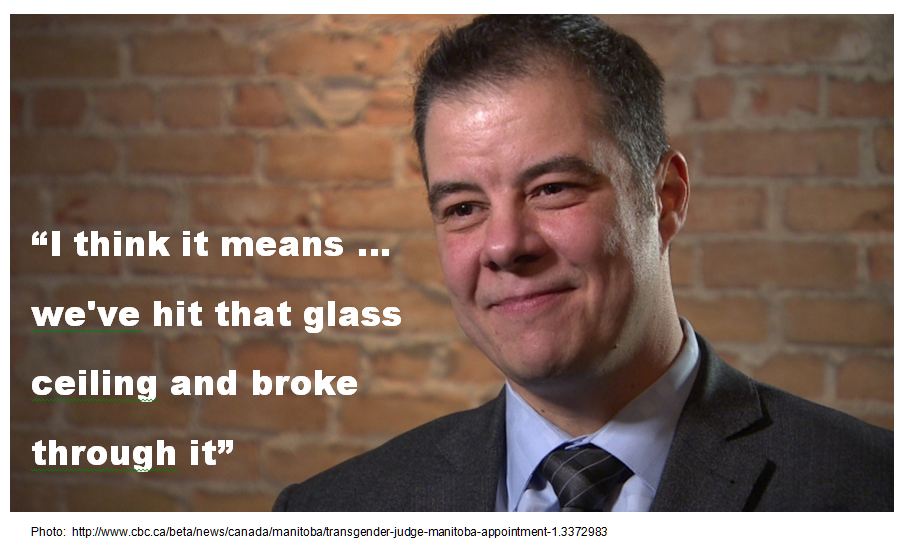

Image: Helping Hands (public domain)